It is the story of one war followed by another war. Yes, it is the…

My Name is Meriam. Trial and Sentence in Sudan

We continue with the publication of the best-selling book by Antonella Napoli, Editor-in-chief of our magazine, for the readers of di Focus on Africa.

After the introduction published last week, the story begins.

Happy reading

CHAPTER 1

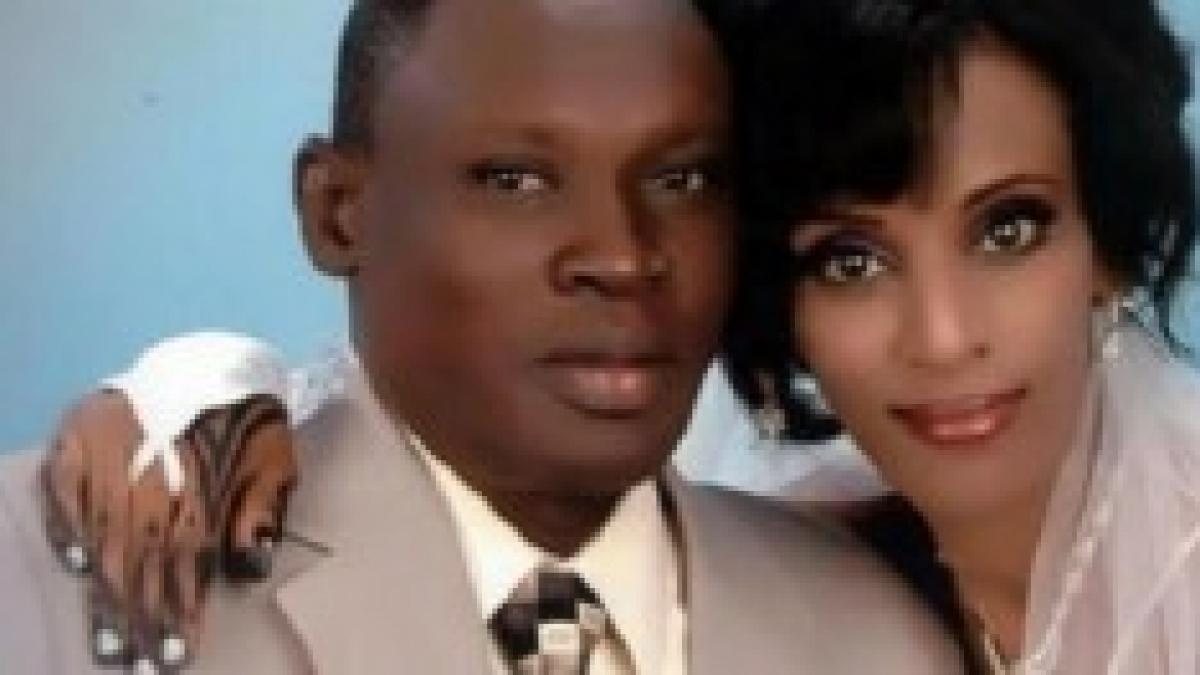

Meriam entered the courtroom slowly. The chains were biting at her ankles, already lacerated by her long detention, and they made a sinister noise, like a lament. But she walked with her head high and a firm and determined look.

When she sat at the defendant’s bench, she glanced up at the higher bench where the man who would soon decide her existence sat. Khartoum District Court Judge Abbas Mohammed Al-Khalifa looked grim, confirming his fame as a hardliner and severe, the strictest judge in the capital city.

“Adraf Al Hadi Mohammed Abdullah,” he asked contemptuously, addressing her by her Muslim name, “What do you say?”

“My name is Meriam, your honor, and I have nothing to add to what I have already stated,” she answered calmly and clearly. “I’m a practicing Orthodox Christian and I have not committed apostasy because I have never known any other religion than Christianity.”

She knew she was going to pay very highly for those words, but the voice of conscious was too loud to keep silent. She had learned to tame fear. She was almost used to braving threats and humiliation. There was little else she could do; the trial had started off on the wrong turn, this was just the culmination of the persecution she had undergone since, months earlier, alleged family members of her father, whom Meriam did not know at all, had reported her because even though she was Muslim, she had married a Christian. They claimed that her real name was Adraf and that she had changed it after she abandoned her family and converted. Her lawyers asked the judge to listen to witnesses in her defense who would testify against the accusations, but the request was overruled. Testimonies in her favor were denied for the entire duration of the trial.

“You were given 72 hours to return to Islam, but you would not accept the benevolence of your Muslim brothers. Therefore, you deserve to be hanged.”

The judge’s words echoed in the courtroom and bounced off the shocked audience in attendance.

Meriam turned to look at her lawyers, and then looked at Daniel.

She was impassive as tears ran down her husband’s cheek. She couldn’t even cry. She looked at the judge, straight in the eyes.

* * *

Rome, 15 May 2014. The unmistakable sound of an incoming Skype call interrupted a conference on racism I was participating at. I had deliberately not turned off the volume on my iPad because I was expecting the call with a mix of hope and worry.

Khalid Omer Yousif, an activist with Sudan Change Now, had just left the Khartoum courthouse where he attended the reading of the sentence. His voice couldn’t hide his profound disappointment: Meriam Yehya Ibrahim Ishag, the pregnant twenty-seven-year-old mother of a one-and-a-half-year-old boy, arrested for apostasy a few months earlier, had been condemned to death.

A few weeks earlier, we had begun a mobilization that had gradually reached the attention of newspapers, television stations, social networks and institutions, and we had fought in hopes that the judge would drop the charges and release her.

The exact opposite had happened.

During the three days of continuance, the “conscience” of whom was making an abhorrent decision that had nothing to do with the law much less justice, had not been raised as we had hoped.

In fact, in answer to the defendant’s refusal, a hard, extremely harsh sentence was delivered.

It was like a slap in the face, a terrible blow to which we responded with all the rage and determination we had inside. A few clicks later, we relaunched the campaign in solidarity with Meriam and against the leadership in Khartoum.

Italians for Darfur, the organization I chair, established in 2006 to raise awareness among the public and institutions on the state and violations of human rights in Africa, and Amnesty International launched a petition and an appeal to send to the president of Sudan, Omar Hassan Al-Bashir, for the immediate suspension of the sentence and to grant Meriam’s pardon.

Word-of-moth went viral on the Net. The Facebook page got over a million hits in only a few days. Activists from around the world, bloggers and ordinary citizens reposted the news. Meriam’s story, a story that was far away yet very near, was not only about her but about all of us, our way of being, interacting and spirituality. It grabbed newspaper headlines and top news stories on television. Indignation was global and the response by the Sudanese government, embarrassed and taken by surprise, was almost immediate.

Abu-Bakr Al-Sideeg, a spokesperson for the Foreign Minister, was the first to intervene. On television, he stated that Sudan was committed to protecting religious freedom under the Constitution and it would do so in the case of Meriam, too. A few hours later, Fatih Adam Al- Din, speaker of Sudan’s parliament, played down the sentence stating that it was a first-degree trial judgement and that the international campaign in support of the woman was actually striving to distort the image of the country and its judiciary system.

The statements, together with media pressure that gave no signs of abating, gave us renewed strength and hope. We knew we were on the right path and after a long night that had lasted too many months, the sparkle of hope began to shine brightly again.

Even Meriam’s lawyers, with whom we were in continuous contact, believed that the sentence would probably change. Mohaned Mustafa Al-Nour, coordinator of the Sudan Justice Center legal staff that included Mohamed Abdelnabi, Osman Mubark, Thabiet Al-Zubier and Ali Al-Sherif, had no doubts: Judge Al-Khalifa had forced the application of Sharia law and contravened the articles in the Constitution that provide for and protect freedom of religion. Furthermore, he said the government had no interest in going forward on such an uncompromising line because it would only result in discrediting the country on an international level and fuel tensions within its borders.

The possibility of a second-degree trial, wherein Meriam would not be tried based on the laws of the Koran and therefore did not foresee the death penalty, took shape day after day. In theory, the Appeals Court judge could very well accept the points regarding the charges provided by the Constitution and change the sentence and fate of the girl, but that he would actually do so was not a foregone conclusion.