It is the story of one war followed by another war. Yes, it is the…

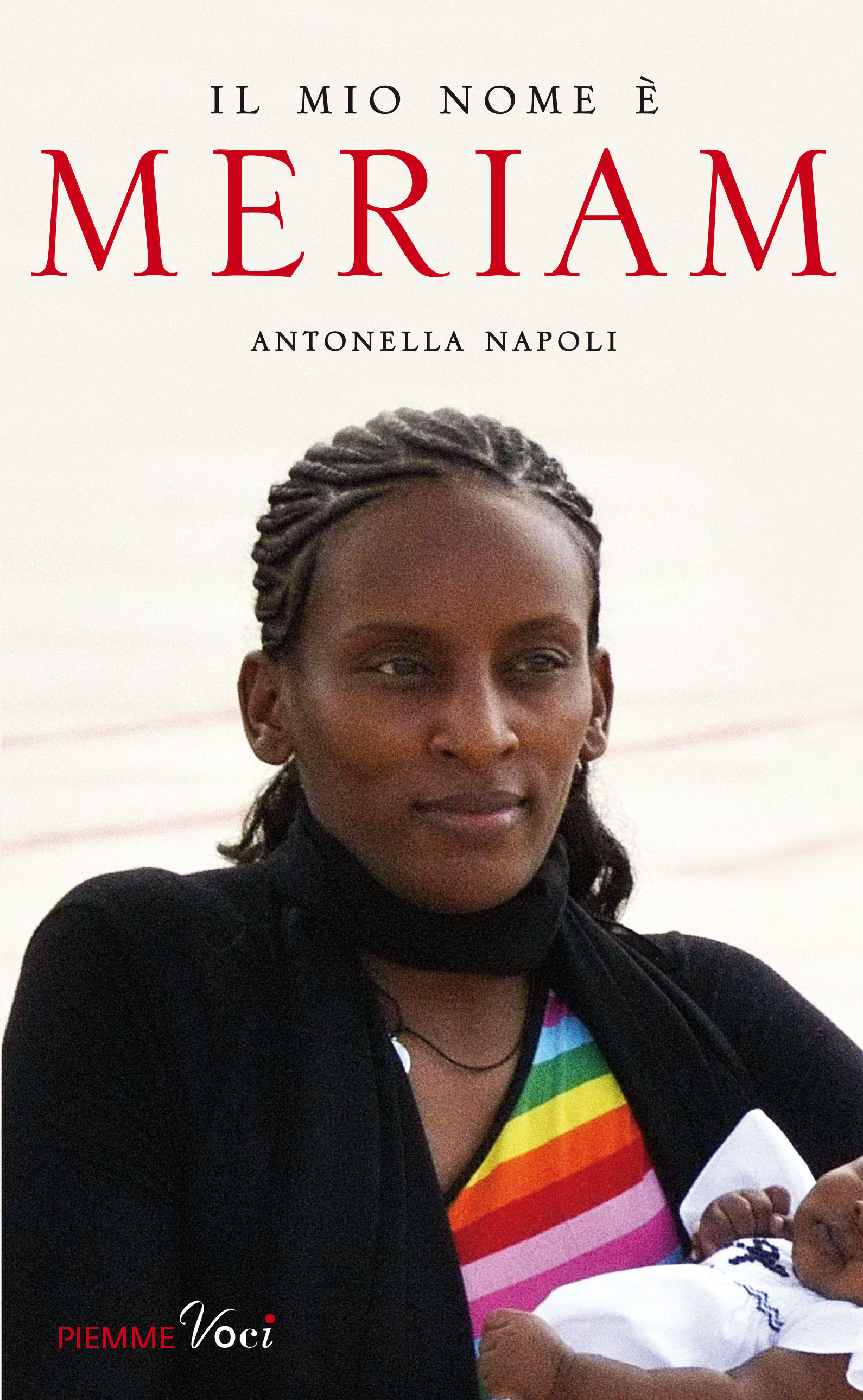

My Name is Meriam, The Story of a Death Sentence in Sudan Becomes a Symbol for Hope

In these times in which we are so distant, we should feel closer and show our solidarity. We have the time to read, explore and think. That’s why I decided to share my best-selling book Il mio nome è Meriam (My Name is Meriam) with Focus on Africa readers at no cost.

I also take this opportunity to remind you that each one of us can do something concrete for others, even from home.

If you haven’t done so already, and if you can, donate, no matter how little, to the organizations that are carrying the heaviest burdens during this emergency. Choose at will: hospitals, the Protezione Civile (Italy’s civil protection department), the Red Cross, Emergency, or any other organization or institution working in the handling and prevention of COVID-19.

I have and, I assure you, I felt much better afterwards.

Happy reading.

Introduction

Not then not ever

When, on a sweltering morning in May, the judge pronounced his sentence condemning me to one hundred lashes for committing adultery and to death by hanging for apostasy, I never imagined becoming a symbol let alone did I aspire to become one. I was only interested in my faith and to respecting the principles with which I had been raised and which I believed in firmly.

Sure, I knew that dozens, maybe hundreds, and even thousands of people scattered around the world were waiting for the court’s decision with baited breath and that most of them could hardly believe that a 27-year-old woman, pregnant with one son, risked the death penalty because she would not renounce her religion.

Despite the fact that diplomatic representatives from the United States, Great Britain and Holland had put pressure on the government of Sudan to respect freedom of religion, including changing one’s faith, under international law the Sudan Constitution, the judge did not back down, not even an inch.

At the beginning of the trial, Daniel, my husband, Sudanese by birth and naturalised American citizen, was confident that it was only a misunderstanding. However, as time passed, he was challenged with the local governments’ intransigence, a deaf and hard attitude perfectly embodied by the president who responded to the ambassadors’ appeal with complete indifference, on the limit of “diplomatic boorishness”, merely stating that judiciary power was autonomous and separate from political power. Therefore, in brief, the government did not intervene.

It didn’t matter that the charges against me were based on accusations by a complete stranger, a man who said he was my brother but whom I had never seen before. And my version didn’t matter either: the fact that I didn’t know that my father was Muslim seeing as he had abandoned my mother and I when I was six years old and so I had no idea that I had committed apostasy. In Muslim countries, religion is passed down from the father’s side and whether I knew my father’s religion or not and had been raised as a Christian didn’t make me less guilty. Sharia law does not allow for ignorance.

Furthermore, I married a Christian so I was also guilty of adultery: a Muslim woman can only marry a Muslim, marriage to a man of another faith is not only inadmissible and not recognised, it is punishable.

Sometime before that, a delegation from the Muslim Scholar Association, that included local imams and religious representatives, paid me a visit in prison. They were not aggressive nor threatening, but they came down on me very hard. They used tones and made assertions that were just as persuasive. They told me they could speak on my behalf in court, they recited passages from the Koran and they invited me to pray with them, arguing that Islam was the most just and compassionate religion and that if I embraced Muhammad’s religion again, I would be awarded with a life rich in satisfaction.

After he sentenced me, Judge Abbas Mohammed Al-Khalifa suspended the sentence and offered me a sort of deal, “We will give you three days to return to Islam,” he said. “If you do so, we will drop the charges against you.” Seventy-two hours later, on 15 May 2014, he wanted to see me. It was a difficult moment, the hardest since the police knocked on my door and took me and my son to prison three months earlier on 17 February.

The judge, dressed in black, with a harsh expression on his face, incapable of showing emotions and even less empathy, asked me what I had decided, whether I had accepted his offer. I refused. He insisted. We went on like this for about forty minutes but I never wavered for a moment. I knew what was at risk and what I would get if I gave in to his demands, but I could not betray my religion, the thing that had made me who I was and gave my every breath meaning. My faith was my strength, my support, the light that shone on my darkest moments. I was sure that the Lord would not abandon me and that he would be by my side until my last breath.

During the reading of the judgement, Judge Al-Khalifa stressed the fact that he had given me three days to recant Christianity but that I had refused. For this reason, he concluded, because I did not appreciate the court’s concession and did not return to Islam, I deserved a severe penalty.I listened without ever lowering my gaze, while outside the courthouse, a small group of extremists heard the sentence and celebrated with shouts of “Allah Akbar”, “God is great”.

In that moment, I didn’t know I was a symbol, and it didn’t matter to me. All I was thinking about was my husband, my little Martin and the life growing inside of me. I was thinking that two words would have been enough to wake me from that nightmare and get back to a normal life. But I knew I would never say them. Not then not ever. I would have taken any punishment to defend my dignity and defend the right to the freedom and choice of religion. Whatever it might be.

Excerpt from interviews with Meriam Yehya Ibrahim Ishag

Khartoum, 7 July, 2014 / Roma, 28 July, 2014