It is the story of one war followed by another war. Yes, it is the…

My Name is Meriam. Chapter 2. Daniel’s Strength. Italy’s Commitment

Daniel Wani looked tried and distraught. Only a few hours previously, a judge had sentenced his wife to death. She had been in prison for three months with their one-and-a-half-year-old son. Daniel did not get custody because the authorities regarded his marriage to Meriam null and illegal, therefore their son Martin and the child that was to be born in a month’s time were considered illegitimate.

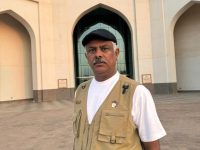

He sat in a wheelchair in the corner of the hall at the prison in Omdurman, a suburb of the capital. He was hoping to see his wife before they took her to her cell. With his right hand, he mauled an old cell phone that wouldn’t stop ringing. He used his other, almost lifeless, hand to manoeuvre the wheelchair he had been restricted to for years because of muscular dystrophy.

His dark skin betrayed his South Sudanese origins, very different from the typical colour of Arab descendants who make up the majority of the population in Khartoum. In 1998, as the civil war tore through the country, Daniel fled Juba, the capital of what is now South Sudan, with his sister and younger brother, and went to New Hampshire, in the United States, where he received citizenship and graduated university with a degree in biochemistry.

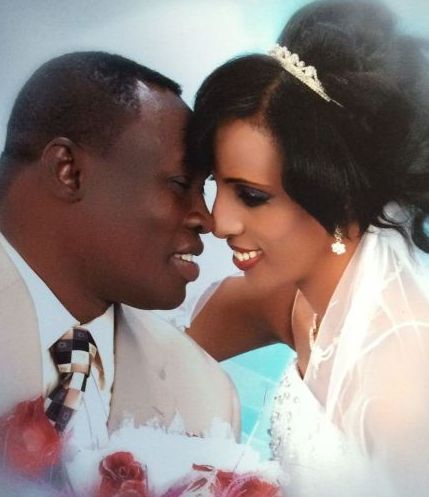

In 2011, he returned to Sudan and met Meriam. They were married in December of that year. She was the most precious thing in his life. Even though he could still move around then, he was completely dependent on her resolute, to say the least, character in all things. Then there was Martin, the fruit of their love, not yet twenty months old and forced to live in a tiny, filthy room full of bugs.

“Since they put him in prison, he’s been sick many times. He looks more and more spent each day,” he said, his voice cracking with worry. “Not not mention the psychological repercussions. He’s a bright boy. Even though he isn’t even two years old, he understands what’s going on, he knows that something is wrong, that he and his mother are not free. Thank God he has a strong will, like his mother, and he likes being with the children of the other detainees, but…”

Daniel was not ashamed of the tears in his eyes, he wasn’t afraid to show his feelings and frustrations. Talking about them was a way to exorsize them. To react. Luckily, even though he didn’t have family in Khartoum, he wasn’t alone. His friends, both Christian and Muslim, supported him and stayed with him as much as possible. Their being there, which made the void left by his wife more tolerable, was fundamental. International mobilization gave no hint of fading away nor diminishing and this also helped him get through the strife. In fact, pressure on the Sudanese government was becoming more authoritative and persistent every day. The display of affection and solidarity filled him with pride. But, at the same time, he knew that all the media buzz could turn out to be a double-edged sword and produce the opposite effects of what was hoped for.

In Sudan, there was tension in the air and it was no surprise when, the day before sentencing, one of Meriam’s lawyers, Mohamed Abdelnabi, received an anonymous phone call telling him to stop defending the infidel and made a death threat. Mohamed did not take a step back. On the contrary, he took two steps forward and committed to the cause with even more determination. Meriam’s case did not only engage him professionally. It called into question religion, freedom, and the highest form of justice. He would not give up for anything in the world, he would not walk away with his head down.

* * *

The online petition launched by Amnesty International and Italians for Darfur collected thousands of signatures in just a few hours. Numerous human rights associations, mainly Catholic, shouted out and the newspaper Avvenire, published by the Italian Bishops’ Conference, relaunched the campaign on Twitter with a simple yet very effective hashtag, #mariamdevevivere (#meriammustlive).

Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi publicly announced his support and a few hours later, Foreign Minister Federica Mogherini took action in an official capacity, placing Italy at the forefront of this battle for freedom.

“I keep thinking about the fact she is a mother, like me,” the Minister confided to Arturo Celletti, correspondent for Avvenire as she was leaving the UN building where she had met with the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon, who said he was ready to take any necessary action to resolve the matter.

“I keep thinking about the child she is carrying and her other child in prison with her. I keep thinking about this atrocious event, about this young woman who is so courageous and determined to defend her faith. The dignity with which she is facing her ordeal should be a lesson and motivation to all.”

Her words were very encouraging. We activists realized we were not alone; politicians had understood that our battle for Meriam wasn’t only her destiny but ours, too, our personal convictions to go beyond the principles we believed in and which, like her, we would never renounce.

After the talk, came the action; solid commitment and support that was anything but random. The Deputy Foreign Minister Lapo Pistelli, sensitive to human rights issues, had been active and determined from the start. The Italian Ambassador to Sudan, Armando Barucco, was at his side. He had started taking action before the sentence was issued and the media started talking about the case. He was in contact with the defence lawyers and because he had a degree in law, he followed the trial proceedings in an informed manner. With grace and expertise, to spoke with the Sudanese team and indicated a possible way the sentence could be reversed and, with caution and discretion, prepared the ground for action for the Italian government.

In the meantime, mobilization was increasing daily and so was media interest and the participation of civil society. Solidarity and the support of thousands of people gave us the strength to face the more difficult moments and keep the feelings of frustration, or even worse, resignation away. Besides, Meriam’s case wasn’t only about her, it was about all of us; we as Christians, Jews, Muslims and atheists. The attack she was a victim of was directed to our personal humanity and humanity in general. At that point, we knew that this was the basis of the trial and so nobody could look the other way. We activists acted as intermediaries, references and eyewitnesses for the collective conscience that was outraged by the aberrant and distorted exploitation of religion. Our defiance was against those who fostered obscurantism and denied human beings their values and their most intimate essence: freedom of religion.

Institutions were on our side from both an idealistic point of view and a material one. At the time, it was important to stick together and leave differences, mistrust and personal interests behind. Shortly after, Italy assumed the presidency of the Council of the European Union and could use the six-month term to launch reflection on human rights, the application of human rights and, above all, how they were being violated.

During his opening address, Prime Minister Renzi did not mince his words and said that Europe could and had to do more, much more. The time had come to take a stand and speak out loud and clear,

“If faced with a case like that of Meriam, sentenced to death for not denying her faith and forced to give birth in prison, Europe does not speak out or, even worse, hides behind empty slogans or rhetoric and continues to lock itself up within its borders instead of reaffirming its values, it would betray what it was established for and it would forever lose its identity, its place in the world. And we would not be worthy of calling ourselves Europe.”