On 29th November 1947, by Resolution 181, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) adopted the Partition…

Mediterranean, The Names of the Shipwreck Victims

The story of the carpenter Vito Fiorino who saved 47 Eritrean refugees from their shipwrecked boat off the coast of Lampedusa on 3 October 2013. The stories of Ambasenger, Amanuel, Solomon and many others, and the steps they have taken on their new journey in Europe.

Last night, a small boat carrying about 50 migrants towards Italy was shipwrecked not far from the coast of Lampedusa.

The newspapers report that the Coast Guard and the Guardia di Finanza recovered the bodies of two women and that 22 lives were saved and transported to Lampedusa. Initial investigations into the tragedy say that the boat capsized and sank while Guardia di Finanza and Coast Guard vessels had already begun to transship people. Another shipwreck, more deaths.

Arrivals, refugees, boats transporting illegal immigrants, drowned, detention centers, immigration management, migration policies, borders, smugglers, safety. Words we see in newspapers every day. Words that generate anxiety and worry.

In 2016, Italy introduced the National Day in Remembrance of the Victims of Immigration. It is celebrated on 3 October in memory of the massacre that took place on 3 October 2013: a fishing boat with a cargo of migrants, almost all of whom were Eritrean – fleeing from permanent military service and one of the harshest dictatorships in the world – sank off the coast of Lampedusa.

Over 360 people died.

It has been defined as “the shipwreck that was supposed to change history”.

The pace of history seems very slow to one of the protagonists of that night. His name is Vito Fiorino, a carpenter from Sesto San Giovanni, Milan. He was on holiday in Lampedusa, on his boat, fishing with a group of friends when he heard desperate cries in the distance. The men navigated in the dark in the direction of the screams and found themselves in the middle of a massacre. Hundreds of people with their arms in the air swallowed up by the sea because they thought they had almost reached safety when they saw the symbolic island of Lampedusa, a portal to Europe, not far away.

Vito was able to call the port authority and drag 47 Eritrean survivors on board his vessel (46 men and one woman) notwithstanding the risk that his own small boat could capsize.

This story is well known. Vito was interviewed about what happened that night many times. He received awards and acknowledgements. In Germany they even wrote a play about his experience. The story of an ordinary man who found himself accidently faced with an extraordinary event who chose to risk his own life and do the right thing.

I interviewed him on the island and in his carpentry shop near Milan a few years ago and we’ve stayed in touch because his experience is still evolving.

The most interesting part of this story, however, is what happened afterwards and the relationship Vito established with the people he saved.

They were bound by tragedy. Those people were about to die and he brought them back to life. They call him “Papà” because he is a father figure to them.

Thanks to him we know their names; who the 47 shipwreck survivors he managed to save are; where they live and what they have been doing since the tragedy. Vito loves them all. He also keeps up with what happened to those saved by other vessels and follows their paths from a distance. But he has kept closer ties with some of them. For example, Solomon and Amanuel as well as Ambasanger and Aregai for whom Vito paid the air fare to Lampedusa on the first-year anniversary of the tragedy so they could participate in the commemoration of the victims.

He uses Google translate to communicate with them. He always regrets not knowing English, but they understand each other nonetheless. Some of the survivors rescued by Vito went to Germany, Belgium and Holland, but most of them were given political refugee status in Sweden where there is a solid Eritrean community and one of the most tolerant integration and reception programs in Europe.

For the first two years the only task the people saved by Vito had was to learn Swedish well. Then they were placed into the workforce. For example, Ambasanger, who was a teacher in Eritrea, currently works at a senior center and Aregai, who was in the army, got his driver’s permit and is now a bus driver.

Many of them obtained family reunification. Furthermore, says Vito, the Swedish government lends refugees money to help them settle into a home so that they can receive their families. They have to pay back the money over the years.

I often ask him how things are going, if there is any news on their progress. “They all have their own car!” Vito responds to give me an idea of how the situation is evolving. “They told me, “ he continues, “that once they learn Swedish well, they’re going to study Italian so they can talk with me.”

Last year, Vito went to Sweden to visit them and see how they were doing.

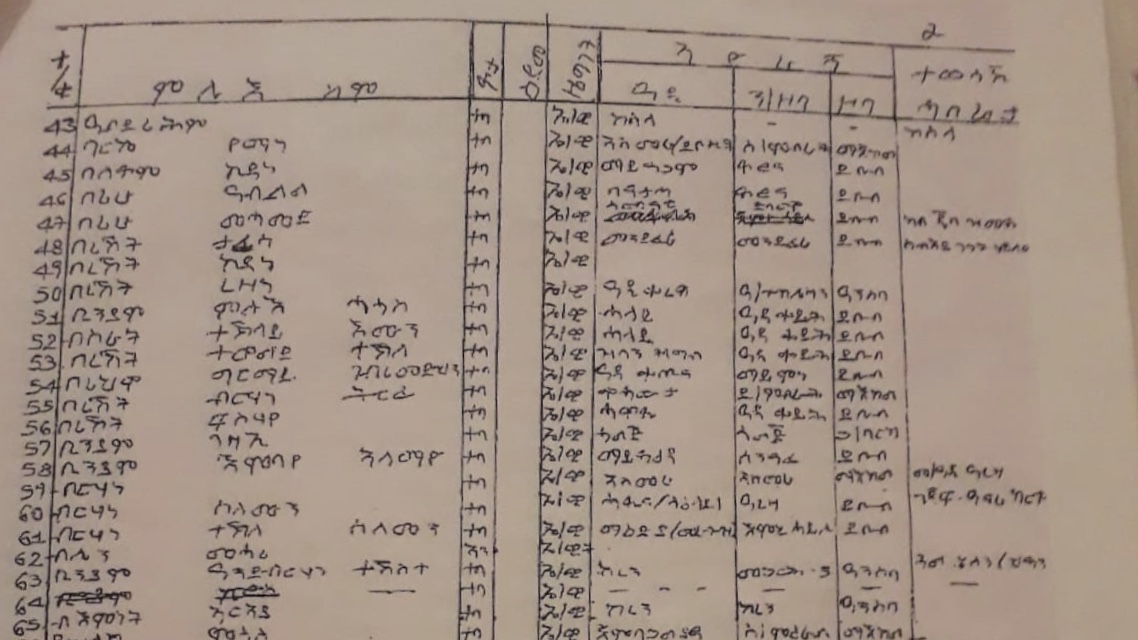

This year, Vito gave them a special task: to write down the names of all their fellow Eritreans who drowned in the shipwreck. After a few months, he made up a list of 365 names (a few are missing. Despite all efforts, they were impossible to find). He then had them etched into a memorial he designed that was inaugurated in the square near the post office in Lampedusa a few days ago. Vito wanted the ceremony to take place at 3:30 on the night between the 2nd and 3rd October, the exact moment in which their boat began to sink six years ago.

The invitation to the ceremony reads, “Lest we forget those who tried to reach a more dignified life and died at sea along with their hopes. To them we owe many answers”.